Do you remember the farm fox expierment? It was a staple study of pop-sci articles a few years ago: the account of the Russian scientist who spent 50 years domesticating foxes. If so, what you probably remember is that even though the researchers bred their foxes only to be more tame, they still ended up looking eerily similar to dogs. Even without context, the results of that study are pretty cool- which is likely why it's such a well known story. However, what you may not have learned is why anyone would devote their entire life to domesticating foxes in the first place.

Like many tales of hereditary intrigue, this story goes back to the Father of Evolution himself. In his 1868 book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, Darwin puzzled over the observation that our domesticated animals all seem to have a highly similar suite of traits compared to their wild relatives, like: white patches on their fur, floppy or smaller ears, shorter muzzles, smaller teeth, more frequent reproduction, curly tails, smaller brains, and more docile behaviour[1]. What makes these shared traits so peculiar is that they have no association with the reason an animal was domesticated, nor with the evolutionary family the animal comes from. How do floppy ears and patchy fur make dogs better at protecting us, sheep better at producing wool, and rabbits more edible? Were the neolithic herders that domesticated these things just really into animals with droopy ears and splotchy tummies? As cute as that would be, it's not our primary hypothesis.

The query plagued evolutionary biologists everywhere, but it took nearly 100 years before anyone would be able to answer it. Enter Soveit scientist Dmitry Belyaev, who realized that the one common factor between every domestication event was that it must have favoured docility. After all, a domesticated animal is pretty useless if it's always trying to attack its handler. Belyaev suspected that all the other strange, unexpected characteristics might be somehow linked to how docile an animal is. So in 1959, he commenced his fox experiment to see if the simple act of breeding for tameness could induce the other domestication-related traits.

His method was a simple one. Each year, he assessed the new kits for tameness, then bred only the foxes that were in the top 10%. In only six generations, the foxes began to display familiar, dog-like behaviours: tail wagging at the sight of humans, whining when their handlers left, and no fear of being petted or held. Within ten generations, things started to get more interesting. His foxes now had floppier ears, curlier tails, more patchy fur colouration, and rounder faces with shorter snouts[2]. By the 1980s, the term "Domestication Syndrome" (DS) was coined to refer to the all the co-occurring traits.

The Biological Basis of Domestication Syndrome

Though this study seemed to answer the question of why domesticated animals have shared traits, the question of how breeding for docility brought them about remained unclear. Belyaev figured that gentle "conditions of living" experienced by domesticated animals reduced their stress and altered hormone signalling, therby reprogramming gene expression and generating all the other linked traits[3]. He pointed to the fact that tame foxes had lower levels of stress hormones, and smaller adrenal glands compared to their more aggressive counterparts.

However, little evidence exists to back up this initial idea. A newer hypothesis proposed by Lyudmilla Trut, the scientist who took over the fox breeding program after Belyaev, suggests that perhaps tameness and the other "symptoms" of DS are all connected in the same genetic pathway.

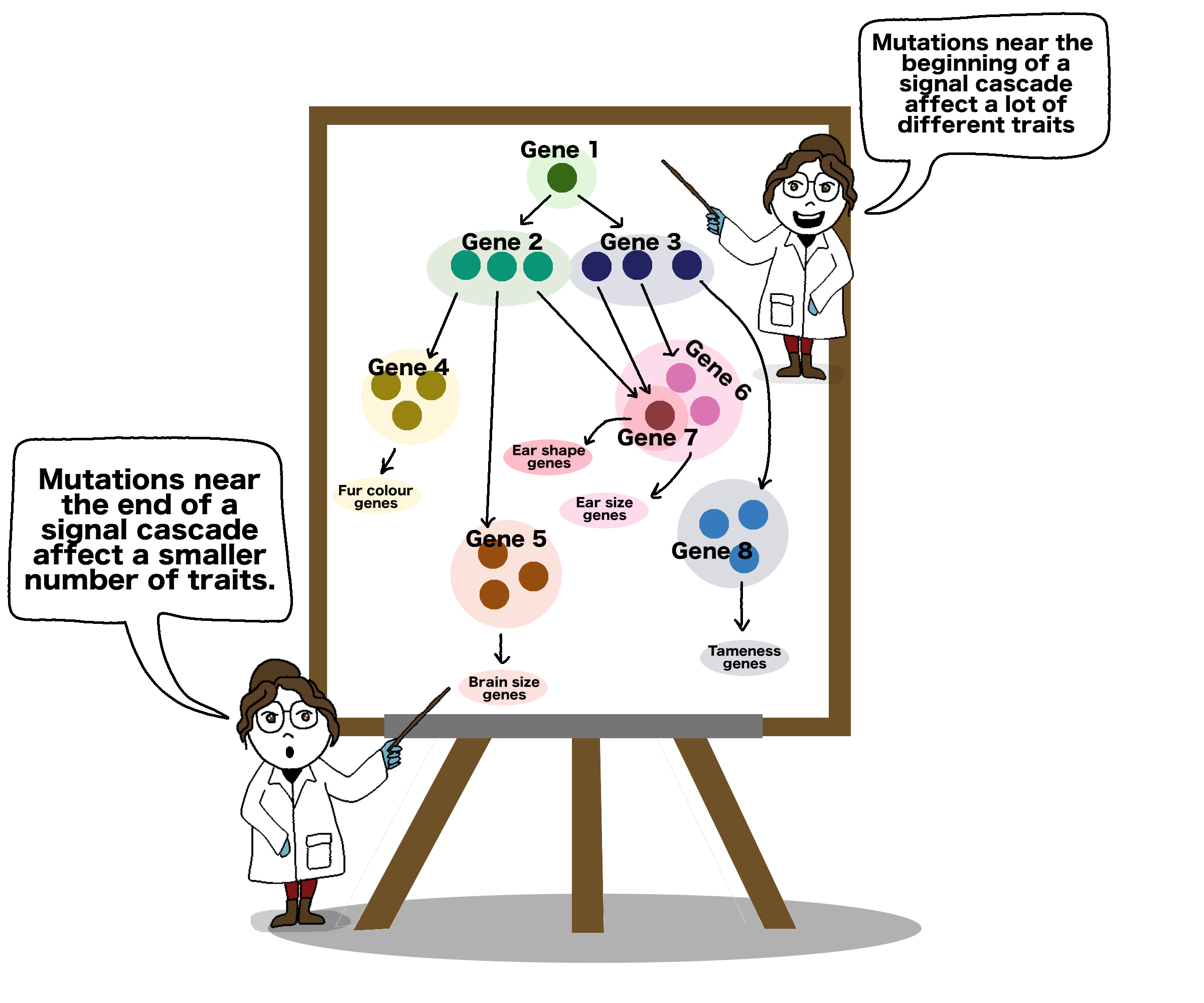

This is not uncommon, especially in embryonic development. Many different traits can be linked together by something called a "Gene Regulatory Network," or GRN. GRNs are a collection of molecules that work together inside a cell to change the way the cell expresses its genes. In turn, alterations to a cell's gene expression impact how the cell develops and functions. In many cases, GRNs act like "signalling cascades." That is, one gene can induce a second gene, which can induce a third, and a fourth, and so on and so on.

Because these signalling cascades tend to become more amplified at each step, a small change in one gene that acts near the beginning of a GRN can have a big impact on the all the genes that act at the end of the GRN. These genes can be responsible for many different, sometimes seemingly unrelated, traits. Thus, the Trut hypothesis suggested that tameness and the other symptoms of DS are all controlled by one developmental pathway.

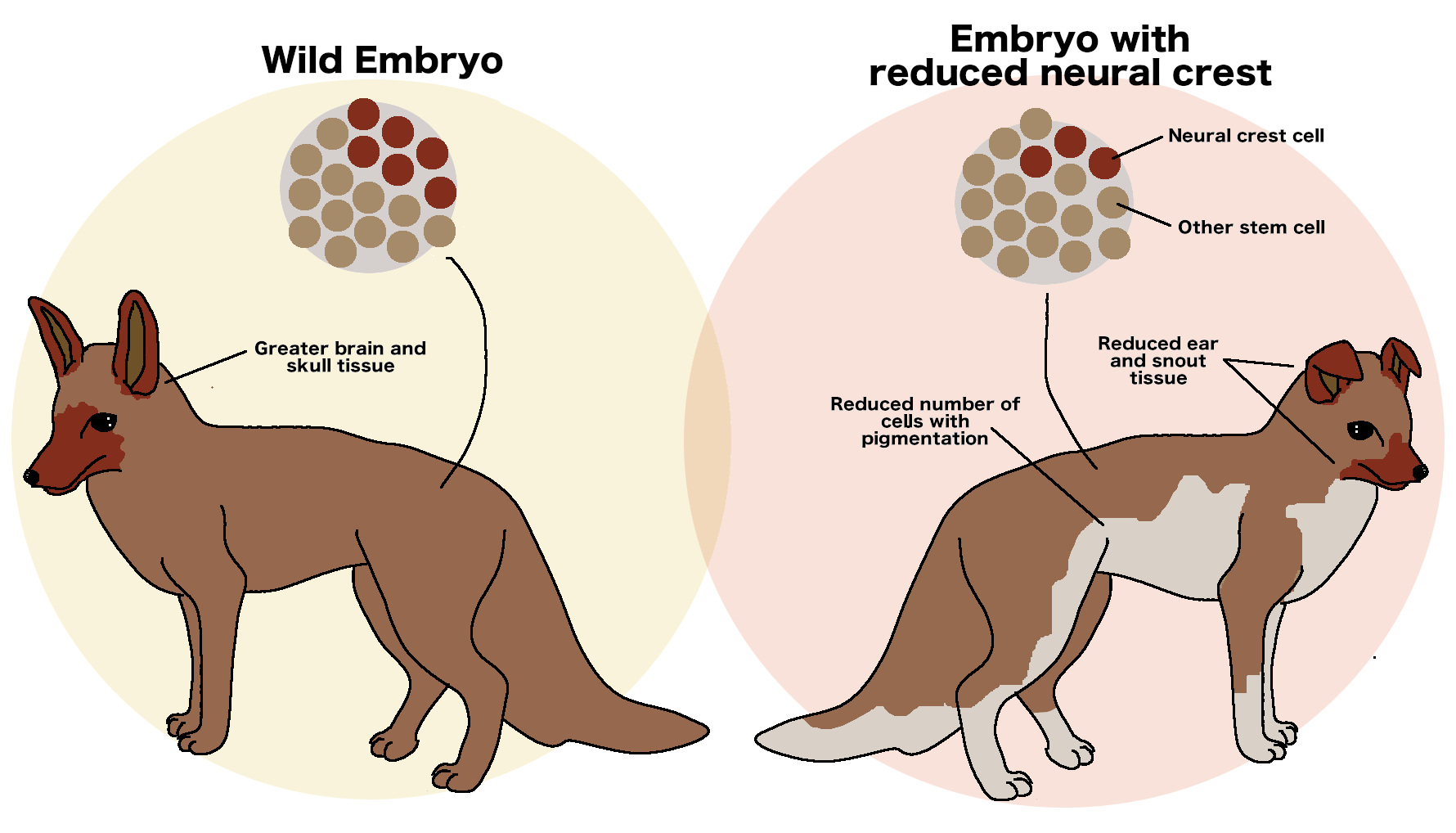

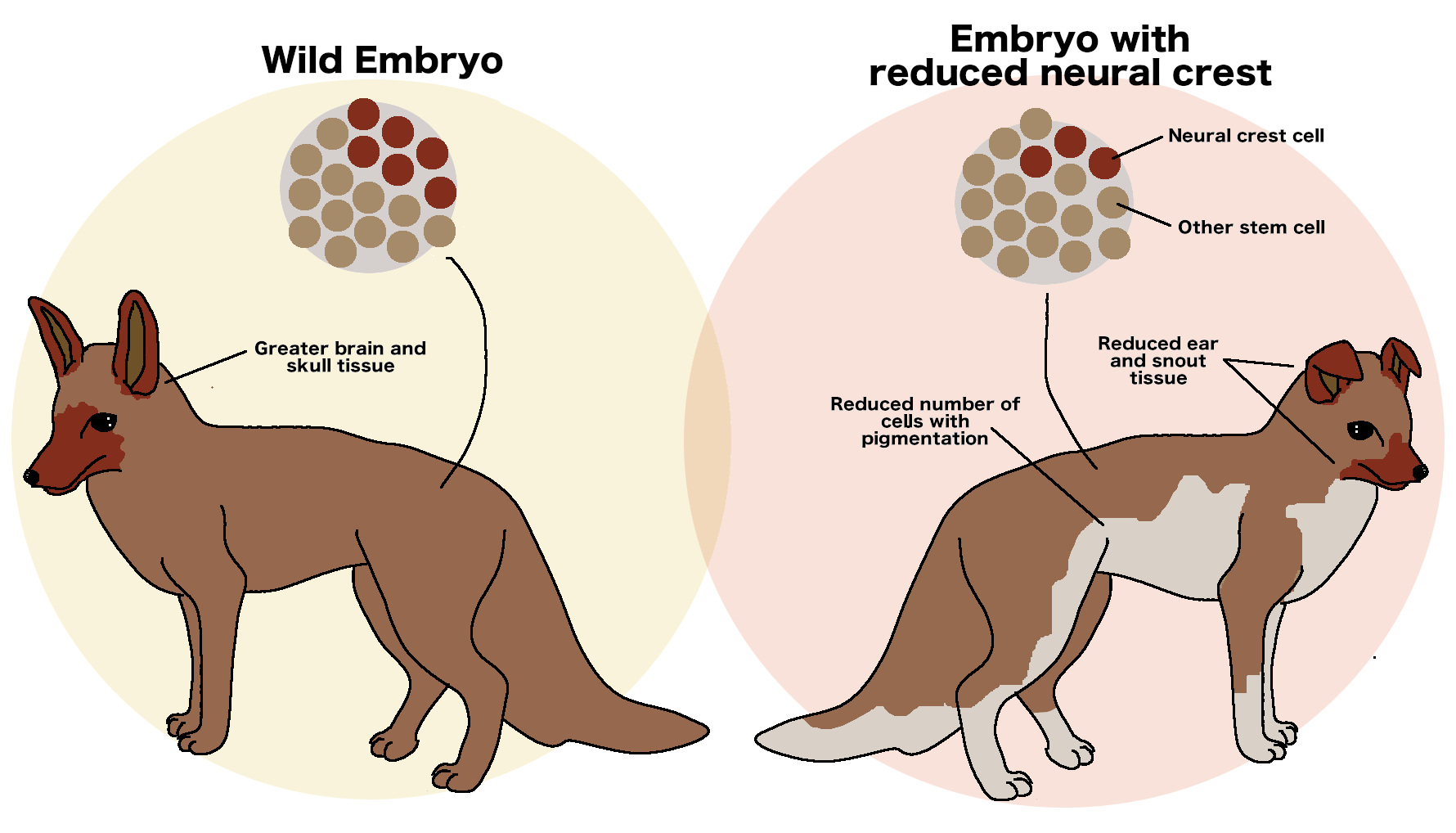

For a long time, this idea was mostly ignored. While it would provide a tidy explanation for DS, genes that act at the beginning of GRNs in embryonic development are so important that even the smallest mutations to them tend to be deadly. The odds that a mutation like this had occurred in every domesticated species seemed almost impossible. Nevertheless, in 2014, researchers at the University of Michigan noticed that the symptoms of DS were found almost exclusively in tissues that originated from the same type of stem cells: neural crest cells. These are a specific type of stem cell that can be found in early verebrate embryos. They go on to become parts of the skull, the adrenal glands, pigment-related cells, tooth precursors, the jaw, and parts of the ears, among many others.

Because tameness is caused by animals being physiologically less capable of feeling fear and anxiety than their wild ancestors, mutations that make individuals more docile generally seem to work by reducing the functionality of the adrenal glands. So, the authors propose that shruken adrenal glands may be caused by neural crest mutations. This could explain why all the other seemingly unrelated traits co-occur with smaller adrenal glands so frequently. Specifically, to reduce the size of adrenal glands, fewer neural crest cells would have to make up the adrenal progenetor tissue in uetero. Thus, the authors hypothesize that if a mutation causes an embryo to have a smaller number of neural crest cells overall, all the tissues that result from those cells would be decreased. This effectively could explain DS: smaller adrenal glands, smaller brains, smaller teeth, less tissue in the ears to keep them straight, and fewer pigment-containing cells leading to white patches.

Genomic evidence seems to back up this hypothesis as well. In a 2018 study that compared dog genomes to those of their lupine cousins, many of the genes that contained strong signals of selection in dogs were related to neural crest development[4].

Still, the hypothesis isn't perfect. For example, it doesn't explain the origin of curly tails. On top of that, there are some experiments that seem to contradict these findings. The tameness of rats doesn't seem associated with fur colouration, and genetic studies on dogs have found that white patches are caused by a gene with no direct connection to neural crest development[5]. Of course, it's possible for multiple different mutations to affect the same trait. Perhaps mutations near the beginning of the neural crest GRN may have created some white patches during initial domestication, and further breeding for fur colouration more recently may have selected for different mutations near the end of the GRN.

Recent Controversy

Despite its flaws, the neural crest theory of domestication is the strongest one we currently have. At the very least, it merrits further study. However, the authors of a controversy-sparking 2019 paper [6] might disagree with that take. The article was touted by the media as a "nail in the coffin" of the theory of domestication syndrome because it argues that Belyaev's experiment was not as provative of DS as it initially seemed, and that domestication syndrome itself might not even be real.

The authors claim that because domestication syndrome does not manifest the same way in every species, it means that it may not even exist. Specifically, they mention that other than tameness, not one single trait of DS is common across all domesticated species. Now look. I know that I'm supposed to be unbiased and simply present information when writing about science. But hey, I'm a molecular biologist! I've read enough literature and written enough essays on this exact subject that I feel like I can take some liberty and editorialize:

It assumes that:

(a), neural crest development is identical in every species, and

(b), that the tameness-inducing mutation in every species is the same.

There's literally zero reason to believe that either of those things would be true. These are all unique mutations occuring in species with distinct developmental pathways. This is essentially equivalent to arguing that a given disease doesn't exist because there's no one symptom that's uniform to everyone who gets it. Come on guys, this is fucking biology. It's one gigantic chaotic mess.

On top of this laughably weak argument that DS doesn't exist, they go on to suggest that the fox experiment fails to prove it for two reasons. First, they note that Belyaev's initial generation of foxes was not fully wild, as they came from a population of farmed foxes that were slightly tame before the beginning of the study. Second, they aruge that Belyaev did not in fact "domesticate" his foxes because they are not as domesticated as other species, like dogs. The paper argues that because the tameness was a trait that already existed in the foxes' gene pools, the experiment makes it "impossible to infer a causal relationship [of tameness] with behavioral selection."

While it is true that correlation is not causation, the authors do not actually provide any evidence to suggest that the fox's traits occured independently of their increased tameness. Moreover, without direct molecular experiments proving a shared genetic basis for all DS symptoms, no experiment can prove it definitively. Indeed, no one is arguing that domestication syndrome is a perfectly proven theory. So claiming that DS simply doesn't exist based on the milquetoast evidence that it has a different presentation in different species is hogwash.

Moreover, the arguments digging at the fox experiment are disingenious to the reality of domestication. Firstly, it is most likely that early domestication events occurred in populations that already contained tame individuals. How and why would people be breeding animals otherwise? Secondly, to argue that the foxes are not domesticated enough is, frankly, patently ridiculous. How could a 60 year experiment perfectly model a process that has been ongoing for over 10,000 years? How exactly do these authors suggest this experiment be conducted? Should Belyaev have invented time travel???

On top of this, it's not even the only evidence we have the DS exists. DS-like phenomena have been seen in nature too. Island populations of mammals often have similar characteristics to domesticated animals. Because animals generally have fewer predators in small islands, there is less natural selection acting to keep their fear response high. Over time, these animals can naturally take on some of the symptoms of DS, such as shorter snouts, reduced brain sizes, and even tameness[5].

Concluding remarks

Despite its controversy, the farm fox experiment continues today under the supervision of Lyudmila Trut. The foxes are more domesticated than ever, and their very existence in the first place represents the very best of what science can be: multi-generational work that aims to ask as many questions as it answers.