|

| Photo of Coca plant by Thomas Grisaffi, from Corona Hits the Cocaine Supply Chain |

If you climb high in the Andes, you may stumble upon an unassuming bush with thumb-sized, elliptic leaves, called Erythroxylum coca. The plant is famous today because it plays an essential role in cocaine production- but this is far from the most interesting thing about it! The story of the human infatuation with coca stretches back nearly as far as the story of humans in South America, and the science of this uniquely influential plant may even give us insights into ancient human history that traditional archeology alone never could.

Though coca contains cocaine, it contains very little. It takes a lot of leaves and a lot of chemistry to turn this humble bush into a deadly narcotic. Most people who chew or drink coca today compare its effects to drinking a coffee, and little evidence exists to suggest that raw coca use has damaging, long-term effects. Indeed, like our obsession with caffiene-based stimulants today, coca was a common favourite amongst a great many South American indiginous groups of yore. The remains of indiginous South Americans from a variety different times and places have been found buried with coca leaves, and coca use is documented on some of the most ancient pottery shards discovered in the region. On top of this, multiple speices of cocaine-producing Erythroxylum were highly cultivated and domesticated by the sixth century CE, suggesting that countless generations of time and effort went into the agriculture of coca. The plant remained important through the Inca period, where it held supreme religious importance, and continues to be an important part of indiginous culture today.

However, for all its popularity amongst Andeans, coca was a New World exclusive. Insofar as we know, the biological capacity to synthesize cocaine is something that only evolved once in the history of life on Earth. It arose as a defense to herbivory in South America after Pangea split apart, meaning that nothing in the Old World can produce the alkaloid. So in 1992, when traces of cocaine were found in the body of a mummified Egyptian woman from 1,000 BCE, historians and scientists alike fumbled for an explanation.

The woman's name was Henut Tuai; a priestest who lived about 2,000 years before Lief Erikson's voyage to Canada, and almost 2,500 years before Columbus. The immediate reaction to the finding was that the supposed "cocaine" was simply misidentified, that it was just a modern contaminant, or that perhaps her body had been replaced by the mummified remains of a drug user from globalized times. However, all of these claims were quickly disproven. Carbon-14 dating confirmed that the body indeed dated back to about 950 BCE, and radioimmunoassays and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry tests repeatedly found cocaine in her lungs, liver, stomach, intestine, hair, bones, skin, muscles, and tendons. Since these samples were taken from inside the woman's body, it's unlikely that there was any "modern contamination."

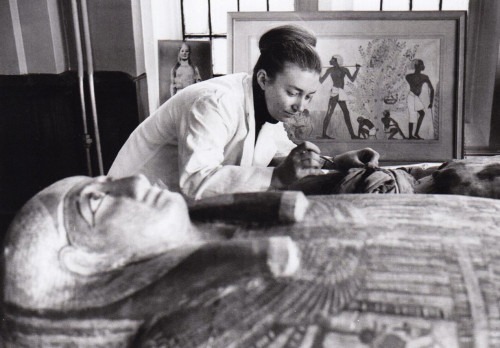

|

| German toxicologist Svetlana Balabanova sampling mummies; photo from beyondsciencetv.com |

Henut Tuai was by no means an outlier, either. Even in 1992, seven other individuals ranging from 1,000 BCE to 350 BCE were found to contain traces of cocaine. In the years following, over 100 mummies were tested, and about a third were found to contain cocaine. Still, critics suggested that perhaps a non-cocaine producing, African cousin of the coca bush, Erythroxylum manii, or another African relative of coca independently evolved the ability to produce cocaine or a similar alkaloid. Perhaps one of these species produces a cocaine-like chemical that can look like cocaine when it breaks down. To date, no evidence exists to back up these hypotheses. No species of African Erythroxylum has been found to contain cocaine, nor is there any evidence of the genus being cultivated or exploitated in Africa. Additionally, multi-year experiments provide little evidence that seeds could have simply drifted across the Atlantic passively. On top of the presence of cocaine in these mummies, nicotine has also been found. Tobacco, like coca, grew exclusively in the New World until the time of Columbus.

After decades of excluding every possible, rational explanation, little but the fantastical remains. Did pre-Columbian trade exist across the Atlantic? Despite the lack of direct archeological evidence, the observation that certain aspects of ancient Egyptian and ancient Meso/South American culture were eerily similar is hardly a new one. Mummification, pyramid building, and trepanning, to name a few, were common on both sides of the Atlantic. More recent work suggests that some crops in the New World at the time of Columbus may even have had Old World origins, such as the African Bottle Gourd Lagenaria siceraria L. and the modern cotton ancestor Gossypium herbaceum L.

Indeed, it's not crazy to believe rare instances of trans-Atlantic passage were possible for ancient humans. After all, ancient people colonized the South Pacific thousands of years ago. The first humans on Hawaii likely traveled about 400 miles further than the distance between Senegal and Brazil, indicating that humans without European naval technology were more than capable of traveling great distances across open ocean.

While we may never know with certainty how exactly cocaine ended up in ancient Egypt, it's clear that our understanding of the chemistry, biology, and genetics of this one, storied, South American plant is challenging historians to question one of the most fundamental paradigms of the way we teach human history. Newer, more powerful science continues to pose questions about our past that traditional archeological methods alone would never even think to ask. Personally, I can't wait to hear what kind of weird, random, science shakes up the historical record next.