Maggja could hardly understand why the Ka chose this crew for such a critical mission. She held her tongue when Frode made the decree in front of his court, and questioning her Ka directly would be an even greater step out of line. “You must trust that there is reason to it,” she reassured herself. “Frode is the wisest man you know.” The words were no servant’s grace either. Frode of Jegersted had been one of Emperor Yorou’s top generals: a legendary strategist with the sharpest wit this side of the Velkyhora. Some of Empress Matlalatzin’s most crushing defeats came by his hands. By the rites of war, the man should have been gored to death in the streets when Jegersted fell. Yet somehow, he managed to parlay his way into one of the highest positions on her council. Reputation aside, the humble spearwoman found little logic in this lackluster group. “Why would Frode choose us to move his only heir across the continent?”

For part, there was no avoiding sending an imperfect team. Reuniting the Empire had been a tough thing for both the Forest Folk of Jegersted and the Oxblood folk in the capital to stomach. Frode was forced to agree to countless edicts that made his people little more than glorified prisoners in their own lands. At any given time, the Imperial roads and waystations within Frode’s province were to be guarded by forces chosen by the Empress herself. It was a restriction no other Ka was burdened with. In turn, it was illegal for the nobles of the Forest Tribes to use their own kin for more than half of their household guard. Perhaps worst of all, the once self-sufficient province was entirely banned from producing its own food. Instead, the Oxborn carted in tubers and pickled fruits from their farms beyond Jegersted’s borders. The rules went on innumerably like that. Even as a high guard of the Ka, Maggja couldn’t come close to reciting them all.

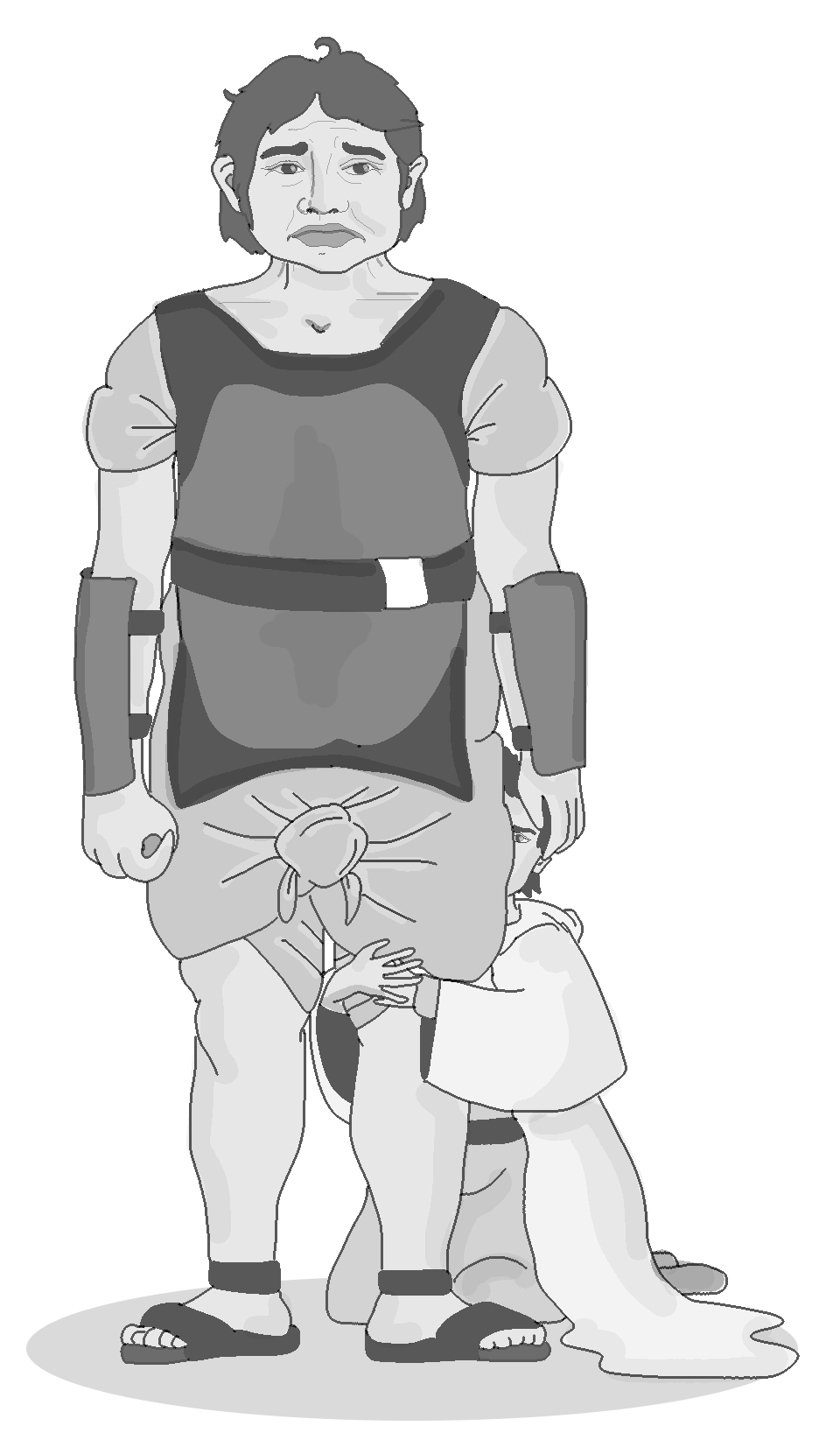

So, it was no surprise to the loyal spearwoman that the Prince’s “diplomatic mission” would necessitate its share of Oxborn guards. And in truth, Maggja couldn’t begrudge the choice of Rendulf as one of her Oxblood companions. The tall, broad-shouldered man was a worthy fighter, a combat veteran of great regard with the scars to prove it. For a warrior of the Yacu, Maggja had always found the man immensely tolerable. What was more, his Ox Chak could carry enough supplies for a month without replenishment.

But why, Gods, why, was the boy Lenuk the second pick? His physical prowess inspired little awe, and the boy was far too young to be battle hardened. Maggja wasn’t entirely sure a single word of wisdom or kindness had ever crossed his lips. Even by his culture’s own standards, the boy was loathsome. He had failed on three separate occasions to tame a wild Ox, a sign of great moral failure in their creed. Maggja wasn’t sure he’d last more than two breaths in a fight, and even less sure he’d have the courage to lay down his life for the Prince if it came to it.

The spearwoman had been chewing over the choice in her mind for the past three days that they’d been walking the Skog Wei, and the only answer she could muster was that Frode simply wanted the odious newt out of his city.

Still, the choice of Lenuk paled in comparison to the ghost-skinned lad Niziro. For a mission so crucial to the future of her people, Maggja expected at least one companion of her own kin. Yet instead, Frode sent some strange foreign boy who’d never once stepped foot in Jegersted: a follower of peculiar Gods with no kinship to her people, even younger and less muscled than Lenuk. She was assured he would be a loyal companion and a more than capable fighter. Yet, the youth did little else but lounge in Chak’s saddle and worry at his flat, black hair with a whalebone comb. That, and disappear for hours each night after they made camp. “It is not my place to question my Ka,” Maggja reminded herself again. The words brought her little ease.

The only thing that broke the Forestborn guard out of her worried thoughts about her companions was her worried thoughts about Lolamard. The Prince had incredible energy for a lad with such short legs. He was always twenty paces ahead of his party, searching the roadside brambles for toads and Rekaberries. Every now and again, the lad would disappear behind a stand of particularly tall fireweed, and Maggja’s tizzying worries would converge into single-minded surveillance. This time, Lolamard had jumped into a ditch, and Maggja could just see his head bobbing up and down behind the tall roadside grass. A moment later, he popped out, holding some great, wide, flat thing between his meagre yellow-brown fingers.

“What have you found this time, my Prince?” the loyal guard called out.

“‘Tis a river turtle!” the boy called back gleefully as he skipped back to show his tribeswoman.

It was a foul beast, truth be told: all scales with the body of an armoured glutton. “Another incredible find, sir, the Great God of the Forest truly blesses you” the gracious spearwoman bowed.

Lenuk snorted cynically, “tHe GrEaT gOd Of ThE fOrEsT.” He waved his hands around his head mockingly.

The smile on Lolamard’s face dropped, and the boy retreated back to the road’s edge. Maggja shot a severe glare at the faithless lout, but the boy snubbed the loyal guard’s disdain as if it were no more than a riverfly bite.

“You don’t fear the gods?” Niziro’s voice was still startling to Maggja, always chiming in with rigid softness at the least expected of times.

“Pfft, what does a foreigner know about the religions of the Empire?” Lenuk dismissed, as if he were some great scholar of philosophy from the libraries of Quilla’ztli.

Niziro lay supine in Chak’s saddle, picking at his nails with quiet ferocity, “how can you be so sure your Gods are the only true ones?”

Lenuk’s wide ears reddened behind his headband, “there are no gods! Only godly men. And demons!”

Niziro sat up slightly, gracing the halfwit sage with a glance. “Is it the act of a godly man to ridicule a nine year old boy, and scorn an entire culture?”

Lenuk’s entire face was red now. He stammered for a response, but Rendulf formed one first.

“Is it the act of a godly man to challenge a lackwit to a battle of words, Niziro?” Maggja chuckled at that, and the foreigner grinned widely before turning back to his muddy nails.

Lenuk huffed, throwing his spear to the ground and crossing his arms. “Enough! I may be the lowest ranking soldier here, but I am still a noble of the Yacu! I will not be treated this way by two peasants and some whaler’s son from across the sea!”

Rendulf stopped his Ox, his thick eyebrows showing the first sign of emotion in days. “Pick up your weapon lad. A true soldier never lays down his spear on duty.”

Lenuk simply blew another exaggeratedly indignant breath, staying motionless, and looking up and away from the rest of the party.

Niziro looked up again, this time with the smile of a child watching a street illusionist’s sideshow.

Rendulf walked towards the protesting boy with a warrior’s gate. It was incredible how menacing the man could be by doing little more than straightening his shoulders. Aside from his flamboyant mohawk and the deep scar across his flat nose, the man had more muscle in one forearm than Lenuk had in his entire body. “When we fought Yorou’s mages at the gates of Tianquiztli, we were boys of all stations in our ranks. Not one of us thought to question the command of their superior officer simply because of his birth,” Rendulf spit with timid vitriol. “‘Tis treason to disobey a superior officer, lad,” he said, touching the hilt of the sword on his back.

Lenuk buckled at that, quickly snatching at his spear. Niziro looked right at Maggja, his half-grin wider than she’d ever seen it.

“Fine,” Lenuk said with reticent sternness, “but it’s my turn to ride on Chak.”

Rendulf rolled his eyes. Niziro pounced to a standing position on Chak’s saddle, prancing off the tall beast’s back with a graceful flip. “Of course, anything for a great noble,” Niziro bowed.

A pleased look crossed Lenuk’s pox-scarred face. He was apparently unable to detect the heavy mockery in Niziro’s tone. The gutless boy gangled oafishly up the side of the saddle, looking rather pleased with himself after finally making it atop.

They began to move again, and it was only then that Maggja realized her Prince was entirely out of sight.

“Lolamard!?” she called frantically. There was no response. She heard the screech of Rendulf’s sword unsheathing, the snap of Niziro’s knives unfolding, but still no response from her Ka’s heir.

“Check behind the brambles!” She barked at her companions urgently. Rendulf and Niziro ran to the north side of the road, and Maggja ran to the south; Lenuk watched wide-eyed from atop Chak’s saddle.

“If this is some jape you’ll regret it until-,” Maggja stopped in her tracks. If only the truth were so agreeable. The Prince was there, still unharmed, but with a knife at his throat. Behind him crouched a scrawny boy with a muddy face, a yellowing bandage over one eye, and long black hair matted into chunks. The abductor peered out from behind the Prince, holding the child in place with a dark olive hand clenching into the boy’s shoulder.

“Drop your weapon,” the scrawny boy demanded, digging his knifeblade ever so slightly deeper into the Prince’s neck.

Maggja dropped her spear, just as the other members of her party ran up behind brandishing theirs. “Lower your arms,” she commanded in a calm breath. The three men exchanged glances, warily lowering their weapons into the grass. Lolamard quivered, the small boy looking smaller still in front of the foe’s much larger body. “What do you want, lad,” Maggja spat with fearful courtesy.

The boy’s working eye peered out behind the Prince’s short crop of wavy, black hair. He couldn’t have been more than sixteen, with the long nose and pronounced cheekbones of a northerner.

“Your food. And the contents of those satchels strapped to your ox,” the boy began.

“‘Tis quite a big price for a farmer’s son,” Maggja ventured.

Lolamard’s receding chin began to quiver, but he had the sense to stay quiet at the lie, despite his paltry age. The captor’s whole head peaked out then. He had a smile on his wide lips, “a farmer’s boy?” The words were drenched in sarcasm.

In a swift motion, the northerner yanked the Prince’s shoulder down, lowered his knife, sliced at the fabric on Lolamard’s back, and tossed a torn strip of the Prince’s red traveling cloak at Maggja’s feet. The knife was back at Lolamard’s throat before she could even flinch. “This is the silk of Tianquiztli.”

“How fortunate,” Maggja thought, “of all the thieving vagabonds on all the roads in the Empire, the Gods have sent us the only one with knowledge of fine textiles.”

“We’re six days from the nearest waystation on foot,” Maggja ventured, “we’ve barely enough food to last that long.”

The boy laughed, “perhaps you have me confused with a person who can be lied to. I’d wager you came from Jegersted just two nights past. Let me make myself clear, your boy can go a night hungry, or he can meet his Gods on the tip of my knife, right now.” The warmness went out of Maggja’s chest at that. There was of course no question that the Prince’s life was worth returning to Frode in failure. But for a whole party of imperial soldiers to be bested by one scrawny boy with a carved bone knife?

Maggja forced a laugh back, “and what? You’re going to fight off four of the Empire’s best soldiers with a glorified deer antler?”

The boy smiled devilishly, pushing his blade ever harder against Lolamard’s neck “would you like to find out?” The Prince squeaked. Maggja caught her scream in her throat, and took a deep breath. “I still have the upper hand. There is still an agreement to be reached here.”“Kuolema!” Niziro cried suddenly, pushing his way past the spearwoman.

The northern boy lessened his grip on the Prince, lingering in the uncertainty for an explanation.

“What in the Gods-” Maggja barely had time to process the situation before Lolamard chimed in.

“Y-yes!” he squealed sheepishly, “I am a Prince of Jegersted!” Maggja all but slapped her palm against her forehead. “If you s-spare me now, I will owe you a d-debt so sacred no God but the Goddess of Death herself could rescind it.”

Maggja felt a chill like none other she’d ever known. “Kuolema’s Dictum? Gods, Frode promised that the whaler’s son would be an asset, but the boy just all but handed the crown of Jegersted to a strange, grimy derelict in order to save us a pound of dried fish and some tin cups.”

“Explain,” demanded the boy with the knife.

Lolamard’s quivering had reached its maximum. Niziro turned to Maggja, “perhaps you can explain better than I?”

The woman exhaled deeply, working on a lie that could rescue the situation, but none came to her. “Kuolema is our Goddess of Death,” she sighed, “making a vow on her honour -- for our people -- it’s unbreakable.” The boy’s face was still clouded with confusion, so Maggja continued, “she- well she chooses where we go in our next life. To break a vow on her honour curses you for all your lives until the end of time.”

Lenuk sputtered a laugh.

The boy’s grip on the Prince tightened, “why does the gangly one snicker?”

“Because he is an impious halfwit who lacks the tact of a common garden shrew,” Niziro shot back coolly, his nearly-green eyes squinting at Lenuk incredulously.

The northerner spun the Prince around, looking so deeply into the child’s eyes he might have been examining his very soul. “Is this the truth as you understand it, Prince?”

He nodded insistently.

“And you vow that if I release you, you will be in my service, you will let no harm befall me at your command?”

The Prince continued nodding with the same veracity. The boy lowered his knife, still holding the nape of the Prince’s tunic in his other hand. He stared at the petrified Lolamard, examining every inch of his face, looking for any hint of falsehood. The hint never came, and after a long, tense, moment the Prince was finally unhanded.

Lolamard scattered away from his abductor, crawling to grab Maggja’s squat, muscular leg. The northerner brushed a clump of matted hair out of his eyes, “well,” he began, sheathing his bone blade across his hip, “where are we going, then?”